Olive, Hardin County, Texas

An Extinct Sawmill Town and the Olive-Sternenberg Partnership That Built It

By W. T. Block

The writer

acknowledges with gratitude the help of Mr. Clyde See, Chairman, Hardin County Historical Commission.

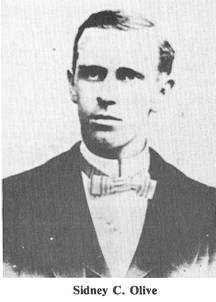

Three

miles north of Kountze, in Hardin County, Texas, where once the burly and

towering pine trees shaded the forest floors beneath them, the town of Olive

thrived between 1881 and 1912. It took its name from Sidney C. Olive of Waco,

who was one-half of the partnership of Olive, Sternenberg and Company, the

owners of the large Sunset Sawmill, which spawned the community. And everywhere

in town could be heard the shrill blasts of the steam whistles, the whir and

shotgun exhaust of the steam-driven log carriage, the whine of the circular and

gang saws, and the screech of the big band saw, sure indications that

mechanization and industry had finally reached “the land of the pineys.”

In

1876, while Beaumont was celebrating the hundredth anniversary of the United

States, the same owners built the Centennial Sawmill on Brake’s Bayou,

Beaumont’s first large lumber mill, and operated it until 1883.

By

1915, the town of Olive, where once some 1,200 people

lived and prospered, had disappeared, having shared the same fate as a hundred

other early East Texas sawmill towns, all of which died when the timber was cut

out and the mill and housing were moved away. Soon, only “cutover” stump lands

scarred the areas surrounding it, and today, its site having returned to

forest, only the abandoned and thicket-covered Olive Cemetery remains to bear

mute testimony to the town’s erstwhile existence. Likewise, all knowledge of

the town of Olive has disappeared, except among a few people of very advanced

years who may have been born there.

In

1875, John A. Sternenberg of Houston teamed up with Sid Olive of Waco to found

the lumber firm, which was capitalized at $56,000. And although both men would

maintain at various times residences at either Beaumont or Olive, they

continued to own their permanent abodes elsewhere, Olive at Waco, where his

retail lumber business was concentrated, and Sternenberg at Houston, where his

other business interests were located.

In

1876, Olive, who was born in Tennessee in 1833, moved his wife Amerika and two children to Beaumont. Sternenberg, however,

boarded at Beaumont’s old Telegraph Hotel, but visited his wife and four

children in Houston whenever possible. J. A. Sternenberg, who was born in the

German principality of Westphalia in 1837, immigrated to Texas in 1849, where he

settled with his parents at New Ulm, Austin County,

Texas.

Following his and his six brothers’ service in the

Confederate Army, Sternenberg moved to Harris County, where he built a steam

sawmill on Green’s Bayou in 1868. In 1882, after their Centennial Sawmill in

Beaumont had been dismantled, Olive moved back to Waco permanently and expanded

the Central Texas retail lumber outlets of the Waco Lumber Company, owned

jointly by himself and A. J. Caruthers, to about thirty-five. Thereafter,

operation of the sawmill at Olive, including all machinery and logging

operations, became entirely the domain of J. A. Sternenberg, as outlined in the

partnership indenture recorded in 1885.

Following his and his six brothers’ service in the

Confederate Army, Sternenberg moved to Harris County, where he built a steam

sawmill on Green’s Bayou in 1868. In 1882, after their Centennial Sawmill in

Beaumont had been dismantled, Olive moved back to Waco permanently and expanded

the Central Texas retail lumber outlets of the Waco Lumber Company, owned

jointly by himself and A. J. Caruthers, to about thirty-five. Thereafter,

operation of the sawmill at Olive, including all machinery and logging

operations, became entirely the domain of J. A. Sternenberg, as outlined in the

partnership indenture recorded in 1885.

Van

A. Petty, who began as company bookkeeper in 1881, soon became

secretary-treasurer of the firm, and was charged with control of finances as

well as the company store and saloon. Petty, who was born at Bastrop, Texas, in

1860, was Olive’s nephew and the son of a Confederate

captain, killed at the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana. Later, one partner’s

oldest son, G. Adolph Sternenberg, became the active manager of mill

activities, and both he and Petty acquired a quarter interest

in the business. Around 1900 and after, two other sons of J. A. Sternenberg and

four of his nephews became associated with the mill, by which time Petty and G.

A. Sternenberg owned the firm outright.1

On

October 10, 1876, Gilbert Stephenson, as executor of the Nancy Tevis Hutchinson estate, transferred the Beaumont

townsite’s “steam mill square,” located where Brake’s Bayou intersects the

Neches River, and bounded as well by Mulberry and Cypress Streets, to Olive and

Sternenberg for $450.2

1Tenth Manuscript Census Returns of

the United States, 1880, Beaumont, Jefferson County, Texas, Schedule I,

residences 40-54, 195; Co-partnership Indenture, Aug. 31, 1886, volume N, Page

9, Hardin County, Texas Deed Records; “Useful Life Came to End: Obituary of

John Abraham Sternenberg,” Houston Daily Post, May 3, 1914; “Built Big Sawmill in

Beaumont in 1875,” Beaumont Enterprise, May 5, 1914; Biography of v.

A. Petty, Sr., furnished by his son, Olive Scott Petty of San Antonio; Obituary

of Sid C. Olive, Waco Daily Times Herald, August 6, 1906.

2volume R, Page 138, Jefferson

County, Texas Deed Records.

Early in 1876, while visiting the Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia, Olive “purchased the prize engine of E. P. Allison

and Co. [sawmill manufacturers of Milwaukee], shipped to Beaumont, [where] it

was the first [sawmill] engine south of the Mason-Dixon line

that had a capacity of 50,000 feet a day.”

Early in 1876, while visiting the Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia, Olive “purchased the prize engine of E. P. Allison

and Co. [sawmill manufacturers of Milwaukee], shipped to Beaumont, [where] it

was the first [sawmill] engine south of the Mason-Dixon line

that had a capacity of 50,000 feet a day.”

Immediately,

the proprietors began building the Centennial Sawmill into the largest lumber

manufactory then in Beaumont. Unlike Long and Company, whose product was

limited solely to cypress shingles, the Centennial Mill installed one

steam-driven shingle machine and three lumber saws, and it took its name from

the centennial anniversary of American independence, which at that moment was

still being celebrated in Beaumont. Sadly, however, the Allison sawmill

depended on an out-of-date, friction-feed log carriage, and it was 1882 before

another Beaumonter, Mark Wiess, invented the steam-driven, “shotgun-exhaust”

log carriage that revolutionized Southern sawmilling. By December, 1877, one

newspaper noted that “the Centennial mill of Messrs. Olive and Sternenberg cut

805,000 feet of lumber last month in 26 days.”3

3Galveston Weekly

News, December

13, 1877; Daily News, December 13, 1877; Biography of S. C. Olive, Memorial

and Biographical History of McLennan, Falls, Bell and Coryell Counties (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co.,

1893), p. 619; W. T. Block, “From Cotton Bales to Black Gold: A History of the

Pioneer Wiess Families of Southeastern Texas,” Texas Gulf Historical

and Biographical Record,

VIII (November, 1972), p. 55; Obituaries of Mark Wiess, Beaumont Enterprise

and Journal,

July 2, 1910.

A

month later, the same newspaper recorded that “the Centennial mill of Olive and

Sternenberg ‘chaws’ up logs at the rate of 40,000 feet a day and employs 20

hands.”4 For the year ending in August, 1878, the six Beaumont

sawmills shipped a total of 21.1 million feet of lumber, of which more than

two-fifths (8.85 million) was shipped by the Centennial mill.5

In

September, 1878, the Galveston Daily News observed:

Another

firm, Olive and Sternenberg of the Centennial mills, are among the prominent

and reliable lumber manufacturers of Beaumont. They turn out nearly 10 million

feet annually. Their planing mills are located in Houston, and the dealings of

this firm are always prompt. Their mills in Beaumont turn out 34,000 feet a day

at present.6

The

1880 Products of Industry census schedule added a great deal of information

about Beaumont’s principal lumber facility of 1879, as follows:

Olive and Sternenberg’s Centennial Sawmill,

Beaumont, Texas. Capitalization, $56,000. Employees,

maximum, 160; average, 60 men and 6 boys as shingle bundlers. Work

hours, daily, 11 winter and summer. Daily wages, skilled,

$3.00 daily; unskilled, $1.50. Annual wages paid,

$22,000. Months mill in operation, 10; shut down for logging, 2. Equipment: one

5-gang saw, 2 circular saws, two 75-horsepower steam engine, 3

boilers. Raw materials: saw logs worth $50,000; mill supplies worth $3,400.

Products: lumber, 9,000,000 feet; shingles, 4,000,000. Value

of products, $88,000. Origin of logs: Neches River and its tributaries — mill did 80% of its own logging.7

One

Jefferson County archival document, indeed, reveals that the Centennial mill

was rafting logs down the Neches River as early as 1879. Because saw logs in

the river belonged to different owners, the lumberjacks and raftsmen branded

logs in the same manner that ranchers branded cattle, and upon reaching

Beaumont, the logs were ‘corralled’ and sorted out for each owner.

4Galveston Weekly

News, January 14,

1878; Daily News, January

8, 1878.

5Galveston

Weekly News, September

23, 1878; Daily

News, September 20, 1878.

6Galveston

Daily News, September

15, 1878.

7Tenth

Census of the United States, 1880, Jefferson County, Texas, Schedule v, Products of Industry, Microfilm Reel No. 48, Texas State Archives, and

recorded by the author in Texas Gulf Historical and Biographical

Record, IX (November, 1973), p. 56.

There

was a code of honor among sawmillers that if a log were delivered to the wrong

mill, the log would be sawn, but it would be measured and proper disbursement

made to the rightful owner. The county’s Log Brand Book reveals that the

Centennial mill registered its log brand ‘S’ on August 4, 1879. 8

Another

news article recorded that the Centennial Sawmill had installed its own planing

mill at Beaumont by 1881. Early in March of that year, A. P. Harris, editor of

the Orange, Texas, newspaper, visited Beaumont and reported everything he had

witnessed in the “Sawdust City,” as follows:

We

visited next the great Centennial mill of S. C. Olive and J. A. Sternenberg,

extensive indeed, and employing more machinery, we thought, than any other in

the City of Beaumont making lumber, shingles, etc., and also running planers.

We met Mr. Olive on the yard… We found

the yard crowded, with material ready for shipment, and two circular saws, the

5-gang saw, the planers, and the other mass of machinery were in full

operation.9

Generally,

the decade of the 1880s presented an unprecedented demand for lumber, and mill

men everywhere made handsome profits, whereas the subsequent decade saw years

of financial depression and limited money for expansion, depressed lumber

markets and curtailed profits. By 1881, a Centennial advertisement confirmed

that the firm was branching out to other lumber manufactures, mainly fence

pickets and cypress cisterns.10 During the

early 1880s, however, periodic low water in the Neches River created perennial

log shortages that adversely affected all of the Beaumont sawmills. In

addition, the infant Texas and New Orleans Railroad, for many years, was unable

to supply sufficient box ears to the Beaumont mills equal to their lumber

output, and the railroad rationed available ears to the mills daily, each

according to its lumber capacity. This was the principal cause for the organization

of the East Texas and Louisiana Lumbermen’s Association, based at Beaumont, in

1881.

8Book of

Log Brands, p. 5, 1879, Jefferson County, Texas Archives.

9“What

the Tribune Man Saw in The Mill City,” Orange Tribune, March 5, 1881,

and reprinted in Beaumont Enterprise, March 12, 1881.

10Beaumont

Enterprise. May 7, 1881, Advertisement of Olive and Sternenberg.

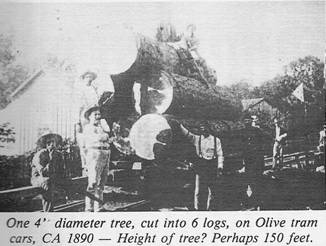

In

1880, the Augustus Kountze banking interests of New York, Denver, and Sabine

Pass, who owned the Sabine and East Texas Railroad from Beaumont to Sabine

Pass, announced their intent to complete the railroad to Rockland, Texas, a

decision that would enable the Kountze Brothers to market their 250,000 acres

of virgin timber lands in nearby counties. Both Olive and Sternenberg began considering the building

of a new sawmill in Hardin County, an area where a thousand square miles of

virgin saw logs, most of them between three and five feet in diameter, would be

available. Logging via their own narrow-gauge tram railway would alleviate the

seasonal shortages of saw logs, which the Centennial mill endured in Beaumont.

They hoped that the Kountze Brothers, with almost unlimited capital to invest,

could break the stranglehold of the box car shortages, once their railroad was

completed. However, as soon as Olive and Sternenberg began planning their new

Hardin County sawmill, the Kountze interests sold out their railroad, its new

right-of-way through “the pineries,” and its rolling stock to the Texas and New

Orleans Railroad, which for so long had failed to supply the mill men with

enough rail cars. As a result, the proprietors made no attempt to sell or

dismantle the Centennial mill until such time as they could determine for

certain how profitable the new Hardin County mill would be. In fact, they

continued to improve and enlarge the Centennial mill at Beaumont during all of

the year 1881.

Even

after the completion of the railroad bridge over Pine Island Bayou and the

first rails entered Hardin County in January, 1881,11 Olive and Sternenberg were already planning the

building of their new Sunset Sawmill and the new Hardin County mill town it

would spawn. At first, they enlarged their partnership, granting a one-third

interest to A. B. Doucette, a well-known Village Creek logging contractor, who

years later, would lend his surname to another mill town in Tyler County. By

1882, the original proprietors released Doucette from the agreement, presumably

at his request, and bought back his interest for $5,600.12

In

March, 1881, their Hardin County plans were set back somewhat by a fire that

seemed so prophetic of conflagrations of the future, described as follows:

The

shed of the [Beaumont’s] Centennial Sawmill caught fire… Wednesday, but by the

exertions of the employees of that mill, what might have been a flaming inferno

was averted…13

11Ibid., January 15,

1881.

12Volume K, p. 30, Hardin

County, Texas Deed Records.

13Beaumont Enterprise, March

12, 1881; Galveston Daily News, March 10, 1881.

Even

before the rails of the Sabine and East Texas reached the new railroad camp at

Kountze, Olive and Sternenberg began shipping cars of lumber to Hardin County

and freighting it by wagon over the remaining miles to the new mill town of

Olive. Mill machinery and supplies followed in August, 1881, and within a few

weeks, one newspaper observed that:

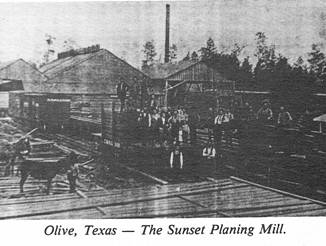

Messrs.

Olive and Sternenberg’s new Sunset Sawmill in the Hardin County pineries, on

the East Texas [rail] line is being pushed ahead to completion. This is an

enterprising firm and deserves every success.14

Three

weeks later, the same editor added: “A few miles farther [north of Kountze],

the Sunset Sawmill of Olive and Sternenberg will cut its first lumber on next

Monday morning.”15 No description of that earliest mill machinery at

Olive survives, but it probably was a duplicate of the Centennial mill’s

machinery, capable of sawing 40,000 feet daily. Cutting equipment installed at

three other new sawmills at Beaumont (although one less circular saw than the

Centennial had) between 1878 and 1880 were identical, a single 5-gang saw and one

circular saw.16

Another

early description of the proprietors’ two mills survives, as follows:

In

1876, they [Olive and Sternenberg] built the Centennial mill at Beaumont, at

that time the largest sawmill in the South, and they operated it until 1883. In

1881, they built the Sunset mills at Olive, which they operated in connection

with the Centennial mill until the latter was dismantled. Since then, they have

turned their whole attention to the Sunset mill, which they have continually

improved and enlarged until it is a first class mill in every respect and

second to none in the state…17

14Beaumont Enterprise, October 1, 1881.

15Ibid., “In the Pineries,” October 22,

1881.

16“Documents of the Early Sawmilling

Epoch,” Texas Gulf Historical and Biographical Record, IX (November 1973), pp. 57-58.

17“Texas Lumber,” Galveston Daily News, July 27, 1889.

In

1880, before the rails reached Hardin County, heavily-forested pine lands, with

virgin timber of four or five feet in diameter, were a drag on the market at 25 cents an acre. As soon as the rails and mills began

to arrive in 1881, the price of timber lands advanced, but there was quite a variation

in price that the proprietors paid, probably because of the distance from the

mill and the amount of tram trackage to be laid. In 1887, they paid from 50

cents to $6.00 an acre for four tracts of land, as follows: to U. M. Gilder,

$150 for 320 acres; to S. B. Turner, $100 for 160 acres; to P. A. Work, $450

for 640 acres; and to East Texas Land and Improvement Company (the real

estate arm of Kountze Brothers, bankers), $1,000 for 160 acres.18

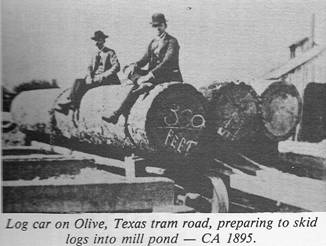

Beginning

in 1881, Olive and Sternenberg faced an unknown facet of the lumber industry

not previously encountered by them — the need

to operate a logging tram railroad. Although they had previously logged the

southeast Hardin County forests for the Centennial mill, all timber removed by

them had been so near to the Neches River and its tributaries that only mules

and oxen had been needed. Hence, after building the Sunset mill they purchased

a locomotive, five flat cars, and railroad iron. By 1889, the Sunset tram was

five miles long.19

By

1887, however, Olive and Sternenberg had grown weary of the logging end of the

lumber industry. On December 31, 1887, they signed an indenture with two

logging contractors, Gustav Linderman and J. S. Davis, to supply logs to the

mill for $2.20 per thousand feet, log measure. The sawmillers agreed to furnish

supplies and maintenance for the tram, and the contractors agreed to buy for

$7,200 all of Olive and Sternenberg’s forest equipment, including 29 mules, 22

yokes of oxen, as well as harness, saws, axes, cant hooks, and sundry items.20

In

1889, the proprietors signed a new partnership agreement, admitting two new

members, each with a newly-acquired one quarter interest, and detailing the

duties of each member. Olive would continue as outside financial agent, buying

all lands and timber and selling all manufactures, much of which went to his

retail outlets around Waco. Sternenberg would continue to oversee operations,

maintenance of mill machinery and the tram road. V. A. Petty, the

secretary-treasurer who had just acquired a quarter interest (half of Olive’s

half), would continue to keep the books, accept and disburse funds, supervise

the company store and saloon and make their purchases, and provide for the

payroll, inventories, and profit and loss statements.

18Volume N, pp. 470, 472, 480, 507,

August 17 to November 25, 1887, Hardin County, Texas Deed Records.

19Galveston Daily News, July 27, 1889.

20VoIume N, p. 529, Hardin

County Deed Records.

Sternenberg’s

oldest son, G. Adolph Sternenberg, who acquired half of his father’s interest, became his Father’s understudy

in the operations of the mill and tram road. The partners set each of their

monthly salaries at $125.21

Apparently,

the four partners established the value of all equipment, timber, and lands in

1889 at $90,500. In his indenture with V. A. Petty, Olive valued his half of

the business at $45,223, and Petty agreed to pay him $22,611 in four equal,

annual installments, beginning in 1890. No indenture between J. A. Sternenberg

and his son is recorded in Hardin County.22

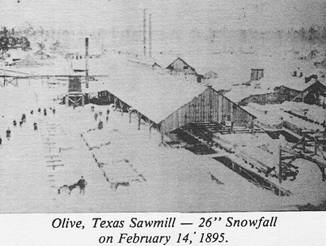

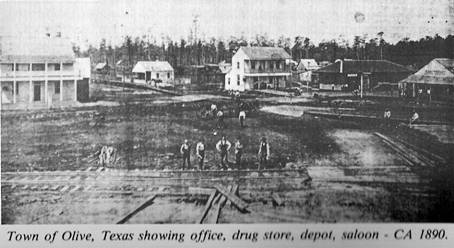

There

also appeared in 1889 the first newspaper description of the town of Olive and its sawmill, as follows:

The

mill is located in the very heart of the long leaf yellow pine section, has a

capacity of 65,000 feet daily, and the lumber turned out is of an excellent

quality. Among the improvements recently added is a large dry kiln, with a storage

capacity of 80,000 feet… Olive has a population of about 500 and is supplied

with schools and churches for both white and colored [people]. Mr. [J. A.]

Sternenberg spends most of his time in a house surrounded by trees, flowers,

and vines, which at this time are laden with all the finest varieties of

grapes, and the company is taking advantage of this fact and now planting a

fifty-acre vineyard, from which good results are anticipated.23

A

year later, the same Galveston News correspondent was back on a tour of

the East Texas sawmills, and he visited Olive during August, 1890. A noticeable

improvement had taken place on the tram road, which by then had reached seven

miles in length and employed two locomotives and 18 log cars. However, mill

employees were back logging the forest, the previous method of contracting the

logging having apparently proved unsatisfactory. The correspondent added:

Within

the past year, many new improvements have been made at this place, among which

may be mentioned a neat little passenger depot for the convenience of the

public, one room of which is a post office, nicely arranged and well kept.

21Ibid., Volume O, p. 555.

22Ibid., p. 562.

23“Texas Lumber,” Galveston Daily

News, July 27, 1889.

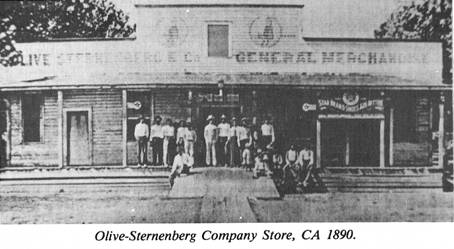

Messrs.

Olive, Sternenberg and Co.,… have just added to their other improvements a large

and commodious business office, nicely furnished with every convenience. Mr. V.

A. Petty, a young man of sterling business qualities, who has been with the

company for eight years, is now not only secretary-treasurer, but also a member

of the firm, giving his attention to the onerous affairs of the office. Mr. G.

A. Sternenberg, the accomplished son of Colonel J. A. Sternenberg, is another

new member of the firm, and keeps a watchful eye on the business of the plant,

which is one of the largest and best-equipped on the line of the Sabine and

East Texas Railway.

The

commissary, which does a large business, is in charge of A. B. Hall, while the

orderly and well-stocked saloon is presided over by W. A. Brooks. The large

force in the woods is under the direct supervision of Mr. Joe Payment… one of the most important men connected with this

enterprise.

Olive

itself is quite a little burg, and is supplied with school and church

buildings, a hall of the Knights of Honor (a fraternal order), also one for

public entertainments. Moreover, it has a newly-organized brass band,

consisting of twelve young men of culture and refinement. The members are Sam

Barnett, the band leader; V. A. Petty, who plays the B-flat cornet; U. A.

Sternenberg, C. F. Sanders, W. Brooks, Arthur Furby,

J. Melancon, A. Miller, and J. Miller. The boys, rigged out in their dress suits

and beaver hats, look charming, and when they go out to play . . . they become the heroes of the hour and the

admiration of the ladies. [For years, the Sunset band played for Beaumont’s

annual firemen’s masquerade and leap year balls.]… One always finds here Colonel J. A. Sternenberg,

who in his vine-clad home, always extends to his guests that generous

hospitality that makes a visit to Olive an unforgotten pleasure.24

Throughout

1890, there was great demand for and an increasing shortage of lumber in East

Texas, which forced up the price by $3 a thousand feet, and left the Sunset

mill with a very low inventory of two million feet on its yard.25 The

market, however, was soon to turn sour as the nation entered a disastrous

depression. Luckily, the decade of the 1890s, due to major expansion of the

American railroads, brought unprecedented demand for railroad crossties, bridge

timbers, and depot materials, which kept many East Texas sawmills free of

bankruptcy as demand for lumber for housing plummeted.

As

an example, in September, 1891, Beaumont’s Reliance Sawmill signed the largest

sales contract, for 100,000,000 feet with the Omaha, Kansas City, and Galveston

Railroad, ever recorded for a Southwestern sawmill, an amount so large that it

would have required the entire output of five sawmills for more than a year.

During 1892-1893, about one-half of the Sunset mill’s output was sold to the

Reliance Sawmill to enable the latter to meet the terms of its contract.26

24“Forging to The Front,” Galveston Daily

News, August 21, 1890.

25Galveston Daily News, March

29 and October 9, 1890.

26Ibid., September 17, 24, 1891; see also

W. T. Block (ed), Emerald of the Neches: The Chronicles of Beaumont, Texas

From Reconstruction to Spindletop (Nederland: 1980), pp. 463,481.

No

information has been located concerning the Sunset Mill’s conversion from the

obsolete circular saws to a double-cutting band sawmill, but the writer

believes that probably occurred in 1898. The first band sawmill in Southeast

Texas that the writer has knowledge of was installed in the new Cow Creek

Lumber Company mill at Call, Texas, in 1895. The following article, although

not specific in mechanical detail, describes the overhaul of Sunset mill during

the summer of 1898, as follows:

Messrs.

Olive, Sternenberg and Co., Olive, Texas, have started up their new sawmill

after a shutdown of six weeks, and now have one of the best sawmills on the

Sabine and East Texas railway. When they shut down on July 15 they put about

thirty mechanics and laborers to work repairing and remodeling; in fact, they

have almost built a new mill out and out… Old

machinery has been overhauled, and modern machinery has been added. The

capacity of the mill has been increased by about 30,000 feet daily… While the mill was being fitted up, a large force

of men, under the management of J. S. Davis, ran some five or six miles of new

tram road to their large tracts of long-leaf, yellow pine timber…27

By

the fall of 1899, both Olive and J. A. Sternenberg decided to retire from the

sawmill business. The latter sold his undivided one-quarter interest to his

son, G. Adolph Sternenberg, for $1.00. Olive released to V. A. Petty his

remaining one-quarter interest in the mill and in 6,670 acres of timber land

owned in common, as well as individual tracts Olive owned outright. By 1901,

Olive, Sternenberg and Company was appearing in deed records as “a corporation

composed solely of V. A. Petty, president, and 0. A. Sternenberg,

vice-president and general manager.”28

The

1900 decennial census of Olive, Texas, reveals that the town’s population was

976 persons, of whom 804 were White and 172 were Black. In both the 1880 and

1900 censuses, J. A. Sternenberg was enumerated separately from his wife

Emilie, but his son 0. A. Sternenberg and daughter Emma, both single, were

living in his household. J. A. Sternenberg had already retired in 1900, listed

himself as a “capitalist,” and reported that he had been married for 37 years.29

27Doings at Olive,” Beaumont Enterprise,

September 17, 1898.

28Volumes V, p. 586; X, pp. 28, 303;

Y, pp. 45, 87; Volume I, P. 149; and 2, P. 63, Hardin County Deed Records.

29Twelfth Manuscript Census Returns

of the United States, 1900, Town of Olive, Hardin County, Texas, Schedule I,

Population, residences 110-112.

The

Sunset Sawmill suffered its worst misfortune after midnight on May 1, 1904,

when the sawmill caught fire from unknown sources and

burned to the ground. The fire was so advanced when discovered that it was only

with great difficulty that the planing mill and lumber yard could be saved. The

estimated loss of the sawmill, which had a daily

cutting capacity of 75,000 feet,

was $40,000, a part of which was covered by insurance. The company soon

announced that the mill would be rebuilt, and to the extent possible, company

employees would be used to rebuild it. Nevertheless, as usually resulted from a

disastrous sawmill fire, many employees found it necessary to move elsewhere

when their livelihoods were severed.30

Two

months later, a Daily News correspondent returned to Olive and left what

is perhaps the best published record of the town and its people. A new

100,000-foot mill was at that moment being built, and “employment is given to

200 men.” The company also took advantage of the shutdown to stockpile logs and

repair and extend the main tram road, as follows:

The

company has nine miles of tram road in operation and is adding more when

needed… In bringing the logs to the mill, four large locomotives are used and

Mr. [M. P.] Hargraves is engineer on the main line. Shay engines are used on

the spurs to bring the logs from the skidways to the main tram… Mr. G. A. Sternenberg is superintendent; Mr. A. G.

Boudreaux, mill foreman; Mr. Jules Berg, planer foreman; Mr. Arthur

Sternenberg, yard foreman; and Mr. J. F. Alexander, woods foreman… There are 5,000,000 feet of lumber on the yard, and

enough timber land is available to last five more years.31

Alas,

the correspondent was already predicting the town’s ultimate fate when the

available timber had all been cut, and only “stump land” surrounded the mill.

He also left the following excellent description of Olive, as follows:

The

town has a current population of 700, of which eighty are pupils of scholastic

age. Public school is maintained eight months in the year, and the school

building is modern in all its appointments. A nice church in which all

denominations have the privilege of worshipping… The

company store closes at 6 o’clock each evening, and the saloon closes at the

same hour… Somebody said it is the only saloon in Texas that observed

regular business hours.32

30Galveston Daily News, May

2, 1904.

31“The Town of Olive,” Galveston Daily

News, July 10, 1904.

32Ibid.

The

reporter wrote most about Olive as a Farming, orchard, and stock-raising

community. He recognized that the town could not always rely on lumber

manufacturing, but seemed to think Olive could always survive as a farming

center, as follows:

When

the lumber interests have gone and boll weevils have made it impossible to

raise cotton, fruit and vegetables will have to be raised as a matter of self

defense… It is a fact that peaches ripened… this year two

weeks earlier at Olive than at Jacksonville and the Bell Commission Co. at

Beaumont… said emphatically that the Olive peaches are the

best that come to Beaumont… Mr. Rufus Harrington raised

five acres of sweet potatoes… [worth] $80 an acre.

Two

years ago, a canning factory was put up at Olive… The

factory is owned by a stock company composed of local people, and has a daily

capacity of 5,000 cans… The company that owns the

canning factory also owns a 25-acre fruit and truck farm one mile from town… Mr. J. S. Davis had 500 head of sheep and recently

he shipped 900 pounds of wool… Mr. John

Holland has 500 head of fine cattle, and others are engaging in hog and poultry

raising… Mr. Guy

Work has 300 head of goats… Mr. Alvin Jones raised eighty

bushels of corn to the acre last year… Mr. V. A.

Petty has a nice fruit and truck farm and will set out more trees soon. As a

fruit and truck growing proposition, Olive deserves liberal consideration…33

Despite

the correspondent’s plea for a rural farm economy for Olive to replace that of

lumber, such was not to be, and the town died with the timber and sawmill. The

reporter’s statements indicate that much time and effort at Olive must have

been devoted to blasting and removing stumps in order to procure the cleared

land necessary for farms and orchards, but in 1904, no sawmill in East Texas

practiced the concept of reforestation, which belonged to a much later time

period.

In

November, 1904, a Beaumont newspaper observed that “the big mill of Sternenberg

and Petty at Olive is now ready to commence work. It has a daily capacity of 100,000

feet.”34

33Ibid.

34“Week in Lumber Circles,” Beaumont Journal, November 13, 1904.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

same editor noted that Olive, Sternenberg and Company cut all of its logs on

the east side of the East Texas Railroad. Although no details of mill machinery

survive, the writer believes that two double-cutting band saws were installed

at Olive in 1904, and that any experienced mill man would agree that nothing

less than two such band saws could cut 100,000 feet daily.

By

1907, all members of the Sternenberg family except G. A. Sternenberg, his wife,

and two children, had departed permanently for Houston. Although only 38 years

of age, he was already entertaining the idea of retiring from active management

of the sawmill so that he could spend most of his time

in Houston, and he soon moved back there as well. To complicate further the

problems of mill management, V. A. Petty moved his family to San Antonio about

the same time. To compensate for their leaving, Petty and Sternenberg brought

into the business five of the latter’s first cousins, Charles A. Sternenberg

and Emil P. Sternenberg, brothers of San Diego, California, as well as

Frederick W. Sternenberg of Paige, Bastrop County, Texas, and the latter’s two

sisters (who were twins), Paula and Annie Sternenberg. The young women were to

be trained as bookkeepers, and at intervals, the three young men were to be

sent to Houston to attend Massey Business College and acquire some background

in business management.35

In

April, 1908, G. A. Sternenberg, while he and his wife were building a new home

and residing at Houston’s Tremont Hotel, contracted typhoid fever and died

after an illness of two weeks.36 Immediately,

his young widow became half owner of Olive, Sternenberg and Company and active

in the company’s management. For some unknown reason, the new proprietors

became dissatisfied with the original firm name, and one of their first actions

together was to deed all community property to the new “Olive-Sternenberg

Lumber Company.”37

For

years the writer has believed (with no known documentary proof that he could

cite) that the sawmill at Olive had shut down in 1907.

A faction of people at Kountze believed that all the buildings there except one

had either been torn down or moved away in 1909. Still others there believed

the end of the town came in 1914.

35Galveston Daily News, April 20, 1908; Beaumont Enterprise,

October 6, 20; November 20, 24; and December 8, 22, 1907; May 5, 31;

October 18, 25, and December 30, 1908.

36G. A. Sternenberg Dead,” Beaumont Enterprise,

April 20, 1908; “Death of G. A. Sternenberg,” Galveston Daily News, April

20, 1908.

37Volumes 51, p. 137, and 54, p.

268, Hardin County Deed Records.

It

is now evident to the writer that the Olive sawmill’s demise came in March,

1912, with most of the people deserting

the town within the next few weeks. The lone, abandoned building which

survived the town by 55 years was burned as a high school athletic prank

in 1968, and is supposed to have contained all of the Olive-Sternenberg Lumber

Company books and records.

The

writer likewise believes that Olive acquired its greatest population, probably

as many as 1,200, about 1905 because a 100,000-foot mill would have required a

work force of 250 or more men to log and operate it. He likewise

believes that the mill operated at full capacity for the next three years, or

at least until the death of U. A. Sternenberg in 1908. Certainly, by then the

scarcity of available timber was growing critical, perhaps necessitating a

reduction in the number of logs processed daily, and requiring the owners to

allow the employees to seek other sawmill employment before their jobs were

severed. Between 1908 and 1910, the proprietors bought up every available tree

that was within reach of their sawmill tram road, either as timber rights or

land bought outright. And certainly, one purchase of June, 1909, was to extend

the mill’s existence for perhaps two additional years. The owners paid

Creighton-McShane Oil Company of Nebraska $18,000 for timber rights on their 3,580

acres of land (5½ square miles) and were also granted a five-year option,

if needed, to complete the logging.38

The

census of 1910 also confirms that life was fast ebbing from the old mill town

of Olive. The census enumeration did not identify the town by name, as in 1900,

but only as “Precinct No. 1,” making it’ somewhat more difficult to determine

exactly where the town of Olive began and ended. However, the writer recognizes

the names of many of the old-time Sunset mill employees, who were scattered out

among the 120 houses left in Olive, and a census total of about 450 persons

(nine pages).39

38Volumes 50, p. 427; 52, p.

349, and 54, pp. 269, 378; also deed record, Creighton-McShane Oil to

Olive-Sternenberg Lumber Co., Vol. 52, p. 346, Hardin County Deed

Records.

39Thirteenth Manuscript Census

Returns of the United States, 1910, Olive, Hardin County, Texas, Schedule I,

Population, Precinct No. 1, residences 155-274.

The

last Sternenberg family members recorded at residence 263 in Olive were Fred W.

Sternenberg, “lumber manufacturer,” and his wife; the former’s cousin, Charles

A. Sternenberg, “lumber manufacturer” and boarder; and the former’s two

sisters, Paula and Annie Sternenberg, each age 26 (twins), who were two of the

four company bookkeepers.” In that age of male dominance in the business world,

they must have been the subject of much conversation, even if they were the

superintendent’s sisters.40 Emil P. Sternenberg was attending Massey

Business College in Houston when the census was enumerated. No division of

duties has been found for Fred and Charles Sternenberg, but it appears that

they shared equal responsibilities for running the sawmill.

Apparently,

many of the old Sunset mill employees planned to remain until the last whistle

blew, as well as others such as Dr. Lee Selman, physician, and Amos Rich,

attorney, both of whom had been in private practice in Olive for many years.

Other employees in the census with long company seniority included John

Holland, locomotive engineer; August J. Boudreaux, mill foreman; B. S.

Fitzgerald and Hugh McDonald, bookkeepers, Jules Berg, planing mill foreman; J.

F. Alexander, woods foreman; Robert Bunkley, yard foreman; A. Bean and Frank

Harper, sawyers; J. F. Richardson and Joe Hargraves, blacksmiths; W. O.

McKennon, store manager; M. P. Hargraves, locomotive engineer; and George B.

Welch, lumber salesman. J. T. Preston ran a boarding house.41

During

the closing years of the town, it appears that the railroad may have chosen

Olive as its southern headquarters for track repairs and perhaps repairs of

rolling stock as well. Among others enumerated there were J. N. Reed, “section

foreman, railroad,” and E. V. Collins, “builder in ear shops.”42

The

author noted a few other items of interest during those closing years of the sawmill

town of Olive. In 1907, a lodge of the Improved Order of Redmen was organized

there.43 A Hardin County local option election in March, 1910,

generated 94 votes at Olive, 54 votes

for and 37 opposed, and that at a time when electors were limited to white

males, age 21 or older, who had paid their poll tax.44 During the

same month, the entire town chartered a train and visited Port Arthur while the

huge sperm whale was on exhibit there.45

40Ibid., residence 263.

41Ibid., residences 161-263.

42Ibid., residences 254, 267.

43Beaumont Enterprise, November

20, 1907.

44Ibid., March 6, 1910.

45Ibid., March 20, 1910.

In

May, 1911, during a Southeast Texas survey to determine the volume of wood

waste products being generated daily, the Olive Sternenberg Lumber Company

reported that it cut 37 tons of such by- products (log slabs, shavings, etc.)

each day, an indication that the mill was still cutting timber at about

half-capacity.46 Perhaps the last thing of local interest to occur

there was the marriage of Charles A. Sternenberg, mill superintendent, on March

1, 1912, a date by which he was surely aware that the mill would be closing

down in three weeks.47

It

is indeed ironic that the beginning days of Olive and the Sunset Sawmill are

better chronicled than the closing days thirty years later. The Hardin County

Deed Records, which usually had bestowed so much information for the writing of

this story, become suddenly silent and especially vague about the last days of

the mill and town. Likewise, there are no recorded contracts, bills of sale,

etc., involving the purchase of mill machinery or its disposal in the Deed

Records. Nevertheless, other sources confirm the closing of the

sawmill in 1912, and one factor in particular suggests that it shut down

in March of that year.

The

long obituary of John A. Sternenberg of Houston in May, 1914, states that “this

[Olive] mill operated for 31 years.” And that figure added to the founding year

of 1881 adds up to 1912 as the year of the mill’s

demise. The obituary also stated that J. A. Sternenberg “had acquired large

property holdings in Beaumont, Houston, and San Antonio.” Earlier, Sid Olive,

who had amassed quite a respectable fortune, died at Waco on August 4, 1906.48

A Beaumont tax list of 1908 verifies that J. A. Sternenberg was a substantial

owner of business property there, rendered for taxes at $31,000.49

For

seven years, beginning in 1905, some one at Olive had contributed a

weekly or semi-monthly social or “gossip” column, published in the Beaumont Enterprise

and captioned “Olive, Texas.” Ordinarily, the columns contributed very

little to the town’s history, usually documenting on the activities, visits,

etc. of a few prominent families. Although the columns appeared three times in

March, 1912, they ended abruptly with the issue of March 25, and did not resume

at any time thereafter.

46“Lumber Products in Greater

Beaumont Country,” Beaumont Journal, May 28, 1911.

47Beaumont Enterprise, March

3, 1912.

48“Useful Life Came to End,”

Obituary of J. A. Sternenberg, Houston Daily Post, May 3, 1914; “Funeral

of S. C. Olive Took Place Yesterday,” Waco Daily Times Herald, August 6,

1906.

49Beaumont Enterprise, May 5, 1908.

An

Olive-Sternenberg document in the archives of the Olive Scott Petty Company of

San Antonio reveals how quickly the mill, town, and business enterprises (which

belonged to the company) disintegrated during the spring and summer of 1912.

The lumber company published a 14-page list of equipment offered for sale and

dated July 15, 1912. Since no band saws, circular or gang saws, or

planers appeared on it, it is assumed these items had already been purchased by

another company, probably Kirby Lumber Corporation. However, such diverse items

as one barber chair and razors (from the barber shop), lots of prescription and

patent medicines, unused corks and bottles (from the drug store), saloon

equipment, and a huge volume of surplus hardware from the company store and

sawmill, typewriters and safes from the company office, and other items were

offered for sale.50

After

1912, there are other indications that the Olive residents disappeared rapidly

until only a ghost town remained, an expected occurrence whenever livelihoods

were severed. According to Mr. Clyde See of Kountze, chairman of the Hardin

County Historical Commission, all buildings were quickly removed or torn down

until only the single building that housed the final office and books of the

Olive-Sternenberg Lumber Company and burned down in 1968, survived. By 1913,

Fred W. Sternenberg, Jr., had moved to Austin (although he remained secretary

of the lumber company for several years thereafter), and Charles A. Sternenberg

had moved to Beaumont.51 Instead of buying more timber after 1912,

the Olive-Sternenberg Company began to sell their limited marketable trees to

logging contractors at $5 per

thousand feet of “stumpage” (log measure), to be cut elsewhere.52

By

1915, however, the lumber company was basically a real estate firm, leasing

tracts of land to oil drillers who contracted to sink an oil well within thirty

days.53 In 1917, the Olive-Sternenberg

Lumber Company, still owned by V. A. Petty and Emma B. (Mrs. G. A.)

Sternenberg, leased 9,962 acres of cutover stump land to Charles Mitchell for

the purpose of oil drilling, and that lease agreement noted that Olive, even if

limited to a single building, was still headquarters of the lumber firm.

50Photocopy, “List of Saw Mill

Machinery, Extra Parts, Supplies, Pipe, Machine and Blacksmith Tools Offered

For Sale, Olive-Sternenberg Lumber Company, Olive, Texas, July 15, 1912,” in

the Scott Petty Company Archives, San Antonio, Texas.

51Volumes 60, p. 130; 69, p. 565;

and 71, p. 600, Hardin County Deed Records.

52Ibid., Vol. 69, p. 192.

53Ibid., Vols. 67, p. 364, and 69, p. 565.

Obviously,

some local person was still in the employ of that company as a land agent, but

any number of deed records checked has failed to disclose his identity.54 As late as 1920, Petty, who subsequently died at San Antonio

in 1929, and Mrs. Sternenberg still owned the firm. And by 1918, V. A. Petty,

Jr., who with his father operated as the Olive Petroleum Co., was also dealing

in Saratoga oil field leases, one of which he sold to Texaco for $2,500.55

As of recent date, much of the forest land where Olive once stood still belongs

to 95-year-old Olive Scott Petty of San Antonio, a son of the

proprietor, who has graciously furnished the writer with much information and

many pictures of the town of Olive, the sawmill, and proprietors.

For

many East Texas oldsters of mill town vintage, the passing of the sawmill meant

the passing of the quieter, simpler, and friendlier days when life was less

complicated and lumber was king of the forest. A stroll, however, through the

brambles, underbrush, and infant tombstones in Olive Cemetery would quickly

remind some passer-by that life in that frontier “sawdust city” had its share

of sorrows as well — an age when only one of two

American children ever lived to reach adulthood. The best-preserved tombstone,

still surrounded by its original wrought-iron fencing, carries the lament in

the German language of a young, immigrant widow, grieving for her husband,

Johannes Nikolaus Paulsen, who died in 1897. And on any still, clear day at

sunset, that same passer-by, provided he has captured the nostalgia that the

graveyard emits, might still hear the faint murmurs of yesteryear’s sobs and

laughter, or catch the distant echo of the big band saw’s screech, as he

silently tiptoes through the pine needles where once the town of Olive stood.

Note of Thanks

(The writer is grateful to Mr. Lee Larkin, archivist/historian of the

Scott Petty Company in San Antonio, for biographies, documents, and copies of

numerous Olive, Texas, photographs a century old and beautifully preserved.)

54Ibid., Vol. 74, p.

197.

55Ibid., Vols.

78, p. 254 and 85, p. 57; also, biographical information furnished by the Scott

Petty

Company archives of San Antonio.